What Is PGT-P? Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Polygenic Conditions

PGT-P is a type of genetic screening available to parents going through IVF that can affect a future child's genetic predispositions. It can be used for everything from reducing a child's risk of autism to decreasing their risk of getting heart disease, to increasing their IQ.

PGT-P is a significantly more comprehensive version of the sort of genetic testing that has been around for decades and has traditionally been used to screen for monogenic conditions like cystic fibrosis.

You can reach out to us here if you're interested in getting access.

What is PGT-P? How does it work?

Since the early 1990s, parents with a family history of a single gene disorder like Huntington's disease could use IVF to avoid passing that risk on to their child. They could go to a fertility clinic, work with the doctor to make many embryos, then implant an embryo that was unaffected by the disease. This worked!

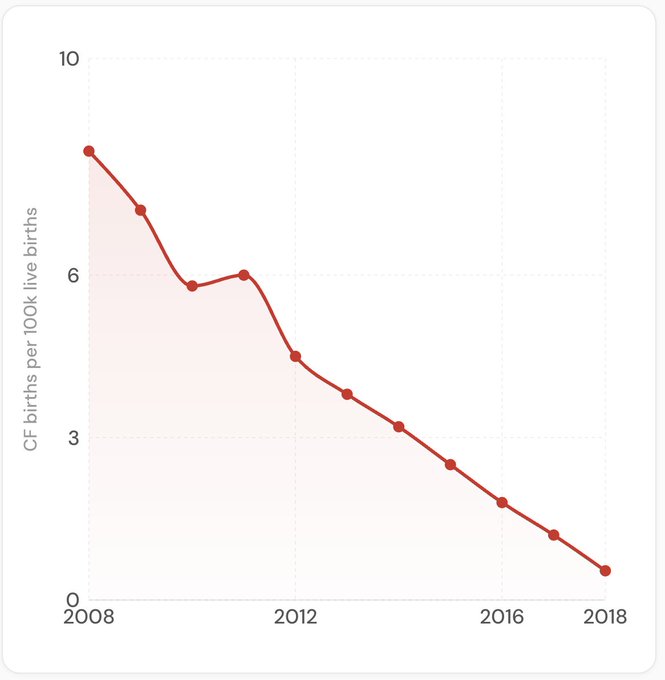

In countries where this kind of genetic screening was widely adopted, the prevalence of these disorders among newborns declined dramatically. In Israel, where screening and IVF were made free for carriers of cystic fibrosis, the prevalence of the disease among newborns declined by over 90%.

Data for this graph comes from Dotan et al. 2024.

This was a huge victory for public health. But unfortunately most diseases still remained out of reach. Conditions like diabetes, Alzheimer's, heart disease, and schizophrenia still couldn't be tested for.

These conditions aren't caused by a single mutation. They're influenced by hundreds of genetic variants, each with a small effect, spread across the genome. You can't just look for one letter change and call it a day.

For decades, we didn't have a way to combine all of those small effects into something useful. That changed as researchers began analyzing the genomes of hundreds of thousands of people alongside their health records, identifying which variants are associated with specific diseases. Once you know which variants matter, you can add up their effects for any individual and estimate their genetic predisposition to a given condition.

This is what PGT-P does for embryos. During an IVF cycle, a few cells are taken from each embryo around day five or six — after the embryo has grown to around a hundred cells but before it's transferred. Those cells are genetically sequenced, and the resulting data is used to calculate a risk score for each embryo, for each condition being screened. One embryo might sit in the 30th percentile for type 2 diabetes risk while another from the same cycle sits in the 80th.

A common objection: "These aren't diagnoses. You can't guarantee anything." True. But it depends what your standard is. If the bar is certainty, no genetic test clears it. Not even BRCA screening. Clinics have screened embryos for BRCA1/2 mutations since 2009. None of those children have reached breast cancer onset age yet. Nobody calls that "unvalidated" because the reasoning is straightforward: genetic variants that predict disease in adults are there from conception. They don't appear later.

PGT-P extends that same logic from single high-impact variants to the broader genetic architecture. Environment still matters. But genetics sets the baseline that environment acts on.

Nature already ran the experiment

Here's something most people don't think about: nature has already run a multi-generational randomized control trial on the effect of genes on health outcomes. Every time two siblings are conceived, the variants they inherit from each parent are scrambled and randomly assigned. Same parents, same house, same food. Completely different genetic risk profiles.

That's INCREDIBLY powerful data. It's why two siblings can grow up in the same environment and one develops type 2 diabetes in their thirties while the other doesn't. People usually explain this with lifestyle. And lifestyle IS part of the story. But the other part is which genetic variants each person happened to inherit.

Your parents' diagnoses tell you about the genetic hand they were dealt. They don't tell you which cards went to each embryo.

Why the validation method matters

This is where the real scientific debate lives. Not whether polygenic scores predict disease — they do — but whether companies validate those scores appropriately for embryo screening.

The most important test of a genetic predictor is whether it can predict which sibling will develop a condition. That's the actual clinical scenario: you're comparing embryos from the same parents, not strangers from a population database.

Most polygenic scores are validated on unrelated individuals. That works for estimating one person's risk vs. the general population. But when you validate on unrelated people and apply to siblings, you get inflated accuracy. By about 40%. That's not a rounding error.

We tested 17 disease scores on sibling pairs. Sixteen of seventeen showed no decrease in predictive performance within families (Moore et al. 2025). That's not "no attenuation for any score ever." It's an honest result on a specific set of scores, validated the way that actually matters for the decision families are making.

Current scores capture around 24% of genetic susceptibility, depending on the trait. The relevant question isn't "is it perfect?" For a high-risk family choosing among five chromosomally normal embryos, polygenic risk scores can shift the outcome by up to 23.5%. And our scores show 28-193% higher accuracy within families compared to alternatives, because we build and validate specifically for the sibling comparison.

What this means for your cycle

If you're already doing IVF, PGT-P adds information to a decision you're already making. It doesn't replace PGT-A or PGT-M. It's a different layer. And with ImputePGTA, polygenic scores can sometimes be extracted from existing PGT-A data, meaning no second biopsy.

There's a situation in reproductive genetics right now where thousands of families are making embryo transfer decisions with less information than they could have. Most clinics still select embryos based on how they look under a microscope. A recent survey of reproductive medicine clinicians found broad interest in PGT-P alongside legitimate questions about validation and ancestry performance. We address those directly: we validate on siblings, calibrate across eight-plus ancestry groups, and publish our methods.

Most polygenic scores were built on European-ancestry data, which means they underperform for other populations. Cross-ancestry calibration isn't optional if this is going to work for everyone.

If you're curious about how much you can reduce your own child's risk, explore the calculator. If you're interested in learning more or using Herasight's screening, please reach out to us.